It’s impossible to summarize a person you’ve known for 64 years into a short essay or biography. So after many weeks of thinking and making notes, this is a glimpse into thewonderful, loving man, I called dad or daddy depending on the occasion or situation.

My dad loved life, mostly everything about it. He loved people, anything to do with people. Playing golf, squash, poker and gin, selling rods and wire, serving on boards and committees, and eating, drinking and laughing with his family and friends. He was full of life, affectionate, robust, and warm. And until the last couple of years, always, always, always positive.

My dad called and visited people in need regularly, sometimes for years. Some of these people were sick or lonely; some were friends and some acquaintances. My dad empathized with them all, even though his life was mostly a charmed one, free of pain and sickness until the last few years he was here.

My dad loved nature. He told me not so long ago that when he was a teen, he used to walk up to South Mountain from his home on Union Street in Allentown. He’d walk alone all Sunday with a backpack filled with sandwiches, cookies, water, and fruit. He said he just wanted to be in the woods and away from the city. He just wanted to be.

My father’s love of fishing was all about being. Being on the water or in the water. Saltwater fishing from one of his boats or surf fishing on the beach or fresh water fishing by a stream or on a lake. When he was in college in fished with roommates on a lake in Maine rubbing motor oil all over his face and arms so that the swarming blackflies couldn’t get through to his skin. He liked adventure.

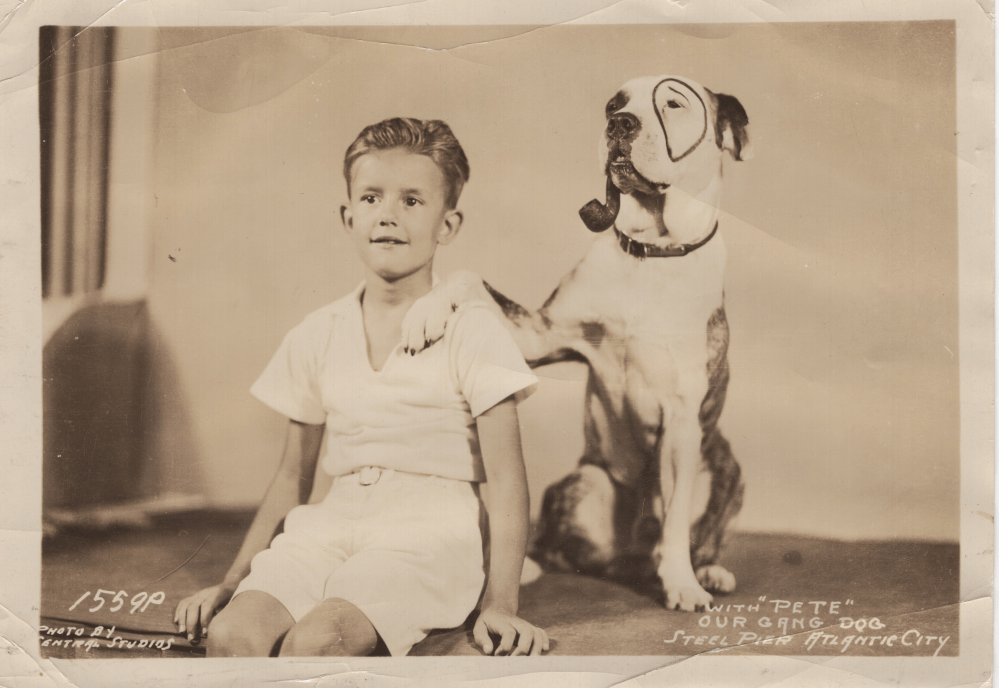

My dad was a fun and funny dad. He taught me to dance when I was two or three, cheek to cheek, holding me in his arms, and twirling me around. Later when I was six, he taught me how to jitterbug. He was a great dancer. He was also a tickling, chasing, hide and seek game playing dad. Roughhouse was one of our favorite games, even though I usually ended up with a bump on the head or a bruised knee or shin. My father never said ‘no’ when my brother or I asked to play. Our dad was a ‘yes’ dad until we became teenagers.

As we grew up, my dad made alone time for each of us children. He took me out to dinner here at Saucon Valley or later at Tio Pepe’s or Libertores in Baltimore. We continued those dinners until a couple of years ago. In fact, our last alone dinner at Saucon was in the Men’s Grill. I remember that evening thinking ‘I wonder if this will be our last time here together.’ It was.

My dad and I were big talkers. One evening, we talked for three hours straight over the phone, each of us with our drinks – dad with his Gordon’s and me with my wine. My mother finally stopped us asking, ‘how can you two talk for so long?’ My dad replied, “If Katie and I were driving cross-country, we’d never run out of things to talk about.” And we never did.

And lastly, I can’t end this piece without saying how incredibly funny our dad was. He could see the humor in absolutely anything. He was a real jokester. Whether it was knocking me overboard when we were fishing, or driving crazily as we water-skied and of course fell down, or hiding my mother’s stuffed mouse from taxidermy class in my bed, or rattling the bathroom doorknob as I was showering in my teens and me screaming every time, “don’t come in” – he was there smiling and laughing in delight. My dad was a happy man.

Now after two plus years of being really sick, my dad is once again safe and sound, strong and laughing. He is with his Mary and all of the others who left before him. Some mornings, as I leave my dreams and float in that middle space between dreaming and waking, I remember my dad is not here. Then I think – he is okay. He is home. I smile and say to myself and to him, I love you, Dad.